Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Maggie Shipstead talks about her extraordinary new novel Astonish Me, why she never became a ballet dancer, the Arctic, and so much more

Maggie Shipstead's smart, funny first novel Seating Arrangements was a national bestseller, a finalist for the Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, and the winner of the 2012 Dylan Thomas Prize. Her new novel, Astonish Me, is something quite different, both a meditation on what it means to be good at your art, and a human drama about love, jealousy and ambition. It's already racking up the raves. The Boston Globe calls it, "elegant and forceful," NPR called it "flawless," and Ron Charles at the Washington Post said, "This is a novel that you must read."

I agree. And I'm honored to have Maggie here. Thank you, Maggie.

Your novel is so different from your first, Seating Arrangements, moving from sharp comedy to the haunting tragedy of what might have been. What was the writing like for you? Did it feel different to switch gears? What surprised you about this particular book?

Astonish Me was probably the most pleasurable writing experience I’ll ever have, mostly because I didn’t set out to make it a novel. I had a fellowship at Stanford for two years, and in my second year I wrote a short story about a retired ballet dancer named Joan and her rivalry with her next door neighbor in California. At the time, I’d also started working on what I thought would be my second novel. After I was done at Stanford and done with edits for Seating Arrangements, I took a break from the novel project to revise the ballet story, and the story started to expand. By the time I finished my initial “revision,” it was ninety pages long, which I think we can agree is a little bit lengthy for a story. I showed it to my agent, and she saw room for more expansion, so I went back to work. It was only about five months between when I started to revise the story and when I finished the sale draft, and for most of that time I felt like I was somehow cheating on my so-called real novel (which has since died) with this funky ballet side project. But then my publisher ended up buying it two weeks before Seating Arrangements was published, and I thought, oh, okay, it’s a book. The accidental nature of the whole process gave me a lot of freedom: I was really writing for my own enjoyment. Astonish Me’s tone is meant to mimic that of a ballet, especially toward the end, and that was a refreshing departure from the prickliness of Seating Arrangements.

Astonish Me is a great title, and though it was said, I believe, by a ballet master, it resonates for lots of other things going on in your novel. Can you talk about this, please?

Yes, Sergei Diaghilev, the impresario of the Ballets Russes, would tell the artists working for him to “Étonnez-moi,” which was sort of a command and sort of a dare and sort of a rallying cry. I think that’s what we hope for out of live performance: to be profoundly moved, to be astonished by what human beings can do. I just read a quote from David Mamet that the point of theater is to provoke “cleansing awe,” and I thought that was exactly right. As you suggested, though, Astonish Me as a title is also meant to speak to those moments of emotional extremity when we’re shocked, even nearly obliterated, by our own ability to feel. When she first encounters Arslan, Joan is astonished by his dancing but also by the intensity of her desire for him. Their meeting is a real bolt of lightning for her. And even the people we know best are still unknowable on some level and remain capable of turning our worlds upside down.

Did you dance yourself? What was your research into the ballet world like?

I danced for a year when I was five. This was not a success. But my mom is a lifelong ballet lover, and she managed to turn me into one, too. We probably saw four ballets a year from when I was five until I was eighteen and left for college. Since then I’ve kept going to the ballet when I can. So I started writing with a decent amount of baseline knowledge for a layperson. But of course I’ll never know what it’s like to inhabit a dancer’s body—I have an entirely different, much more mundane relationship with my body. I was traveling when I was writing Astonish Me, and I lugged a hardback ballet reference book with me, but mostly I relied on the extremely portable internet, especially YouTube. For every variation I included in the book, I watched and re-watched multiple versions: different dancers, different eras, different productions. I watched behind-the-scenes videos that some companies post of rehearsal and class. I watched documentaries and listened to how dancers described their experiences. Then, unavoidably and alarmingly, I had to imagine the rest.

One of the more aching things about your novel is the whole idea that someone could be good, but not quite good enough to be a star, and what that means and how we deal with that. Is there a way to deal with such a thing, or are we condemned to always yearn?

I think most artists are probably condemned to always yearn to be better (or more celebrated), but I think acknowledging that yearning is helpful as far as dealing with it. My work is never quite what I want it to be, but I’ve made something like peace with always being a little disappointed with myself. If you’re an artist and you think your work is perfect . . . to me, that’s a red flag. I don’t think that kind of self-regard is good for anyone as a human, and I doubt it’s great for the quality of anyone’s work, either. Isn’t the striving part of the point? For some people, though—and maybe this will be me at some point—the process stops being meaningful enough to justify the frustration.

What’s your writing life like?

For the past few months, my writing life has been pretty nonexistent because I’ve been promoting this book. Hopefully I’ll be able to get back to work pretty soon, though. When I’m really working, I usually work six or seven days a week. I don’t have a strict schedule. I’m not a morning person, so I usually get up around nine and then fritter away a few hours walking my dog and having breakfast and checking to make sure the Internet is still there. I usually work in the afternoons and evenings. I like to leave the house if I can. Writing Astonish Me, I was in Paris for three months, and I usually went to Starbucks. That sounds so lame and unromantic, but they let you sit there forever and they have outlets and giant coffees, which most French cafes definitely do not. I’ve written both my books during periods when I was living places where I didn’t know anyone and had a lot of time and solitude to work with. My challenge now is to figure out how to be productive and also have something resembling a social life.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

The project I’m working on now involves both the Arctic and the Antarctic, so I suppose I’m obsessed with unforgiving landscapes and the general scale of the earth. I’m in the UK at the moment doing stuff for Astonish Me, but I’m heading to Norway next week, eventually making my way up to the far north and then flying way up into the High Arctic to a group of islands called Svalbard. There’s an organization that runs a trip aboard a tall ship for artists interested in the Arctic. So I’ll be sailing around Svalbard for the second half of June. I would really like to see a polar bear.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

Can't think of a thing!

The fabulous and funny Nick Belardes talks about A People's History of the Peculiar, being psychic, being impatient, and all things bizarre

A People's History of the Peculiar is a most wondrous book, full of strange facts you really need to know, all of them guaranteed to delight, shock, and just tickle you. Nick asked me to write the foreword, which was one of the most fun pieces I ever wrote, and I'm frankly honored to be associated with anything Nick writes.

Nick, you are too cool for school. Thank you for coming on my blog!

So what sparked the idea of this book?

Years ago

I’d been on a writing panel with Brenda Knight, author of Women of the Beat

Generation at the Yosemite Writers Conference put on by author Bonnie Hearn

Hill. When Brenda went to work for Cleis Press she helped launch the mainstream

imprint Viva Editions and asked

me to write a quirky book. I can’t even begin to describe how interesting

Brenda is. She once called me a spider shaman after I survived a black widow

bite. Allen Ginsberg came to one of her readings (one of the weirdest and

coolest American poets ever), and she has bizarre ties to the Mothman story (I

go into detail about this in A People’s History of the Peculiar). She’s had great success with Viva Editions. Some

of her clients have gone on to Oprah fame. Some are exciting word-lore lovers

like Arthur Plotnik (The Elements of Expression and Better than Great: A

Plenitudinous Compendium of Wollopingly Fresh Superlatives) and philosopher-writer

Phil Cousineau (Wordcatcher and The Painted Word). So, how could I say no? I

studied and taught history, so that’s why there’s so many weird tales from the

past in the book. I think the truth of it is Brenda collects authors who hunt

knowledge in strange ways and I’ve fallen victim.

What really surprised you in your research? And how

did you ever stop researching with amazing facts like these?

I think what

surprised me about researching A People’s History of the Peculiar was how

accessible the weird really is. Strange stories from the past, weird disease,

weird science—all easy to dig into in university library archives and internet

news stories. I was amazed how willing people were to talk about the bizarre

stories they’re connected to when I called to interview them. Scientists

examining Teddy bears in space. A man who has Alice in Wonderland Disease. A

guy obsessed with animation who worked on one film for four years. Really made

me think how we’re all utterly connected to this strange cosmos. Look at

writers. You’re weird. You searched for inter-dimensional portals as a kid. You

probably have all kinds of writing habits that people might think are

ripsniptiously strange (You see? Arthur Plotnik taught me that cool word). I

was obsessed with books, maps and clay as a child. I mean really obsessed. I

built entire clay armies and giants out of clay too and waged epic wars. Each

clay soldier was armed with a toothpick sword. The giant? A butterknife!

Caroline . . . I’ve never stopped researching. I can’t. There’s a man who lives

though he has a flat brain. There’s a little part of a cell called a telomere that

tells us how long we will live (I don’t want to know). And Mateo Ricci in the

16th century taught the Chinese how to build memory palaces. I can’t

stop finding these facts so amazing.

Why do you think truth really is stranger than

fiction?

There’s a

story in A People’s History of the Peculiar about a man with Cotard’s Delusion.

He thinks he’s dead. He wonders why the clocks are still working. Shouldn’t the

ticking have stopped? What an interesting POV he would make for a novel. But

would it fly? Maybe this has already been done. Maybe it’s too weird to pull

off. Of course I know how weird novels get, how the worlds we build can create

any kind of believability in the reader’s consciousness. But would anyone want

to journey with such a narrator? Perhaps. Either way, Cotard’s Delusion is

real, and so is Capgras Syndrome where people think everyone is an imposter,

including their pets. Have you ever thought your turtles were imposters,

Caroline?

I know the answer to this, but I want your

answer--why do you think people absolutely NEED a book like this? (And need it,

they do.)

Every toilet

needs a book next to it (Throw away those People Magazines for some real kooky

knowledge). Every date needs a spark of weird conversation, like, “Did you read

about that wastewater job guy who rebuilt photos of people flushed down the

toilet? Remember that nude photo of me you ripped up and flushed? Thanks a

lot!”

What's your writing life like?

Every project

requires unique sorts of channeling of knowledge or characters. Some books I’m

more excited to write the rough draft. Others I prefer the research or

revision. I don’t write everyday. But when I know I need to get a project done,

suddenly I’m in a trance. I’ve fallen through that portal you were searching

for as a kid that you talk about in the foreword to A People’s History of the

Peculiar and I’m in another dimension. I insanely write and words pour out

through an invisible spigot of the imagination. I start logging my word counts.

A thousand words a day. Five thousand words a day. Some days upwards of ten

thousand. Ros Barber, who wrote The Marlowe Papers (a novel all in verse), once

told me a great writing day for her is one hundred words. What? Can you believe

that? I think for me, because I prefer fiction, it really depends on the

question of have I propelled the story? Has the character done what he/she set

out to do? Are they tormented enough? Does my scene have a beginning, middle

and end? For A People’s History of the Peculiar it was more about, did I

capture the essence of a few interesting tales of the bizarre? That book was

written in two months. I was obsessed with finishing it. I had to get a certain

amount of strangeness out each day. Bam. Done. Next freak show tale. I should

also add that I love to write in interesting places. Homes. Universities.

Coffeehouses. There’s a dark inter-dimensional time portal at Texas State

University called Boka’s Livingroom where I wrote half the novel Big Spoon,

Little Spoon that my agent is currently pitching. I love that place, though

most writers I’ve met say they loathe the darkness.

What's obsessing you now and why?

I’m

impatient. Aren’t all writers? I have yet to meet a patient one. Not a single

creative writer has a lick of ability to wait for anything. When’s the band

gonna start? When’s the movie gonna begin? Even while channeling characters

it’s like wrestling spirits. Oh, now they’re all reading this saying, “I do! I

have patience!” Liars. Every single one of us is an impatient liar. I propose

that for at least the next few moments we all admit to ourselves that we are

impatient to see our next love, whatever that may be—fiction, nonfiction,

poetry, screenplay—turned into what we intended it to be—a finished product. A

book in our hands or a film on the big screen. This obsession has me waiting impatiently

as my agent pitches Big Spoon, Little Spoon, a novel about a brother and sister

living on an island in a river. You see, where I’m from in Bakersfield,

California, the Kern River, which is a very deadly river, passes right through

town. When the water’s flowing there are islands that people live on, where

cops I call Robocops (and so does the narrator) sometimes come in with knives

and shred the tents of the homeless. I’m obsessed with this particular novel

selling. I want the narrator, a boy named Sugarfoot, and his sister, Tender, to

be able to speak to people all over the world. Can you tell yet that I’m

obsessing? I was obsessing recently over a counterculture memoir set in the

1990s, but decided to shelve that again to obsess over a literary fantasy

titled A Serendipitous Garden of Lies, a project currently more worthy of my

time. Characters from that novel are really speaking to me and want their

stories told. They are poking me in the nose as I type this. All of those

characters have their own obsessions, and now it’s my job to help all of us

obsess and be tortured.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

The other day I was lucky enough to be a guest on Coast to

Coast AM with George Noory when someone named Marty called in. Marty was

clearly disturbed by our conversation of Salem witches and talking dogs and the

maidservant Tituba declaring she could fly around on a stick.

Marty: I happen to be a redhead . . . And your guest was talking about the Salem Witch Trials. I always assumed redheads were witches. And I was always really concerned about that.

George: Has anyone ever called you a witch, Marty?

Marty: I do have some psychic powers . . .

I suppose the question is: do I have psychic powers? And the

answer is yes, an emphatic, yes.

The fabulous Jon Clinch talks about Belzoni Dreams of Egypt, being unpredictable, fictional autobiography, and so much more.

I so deeply admire Jon Clinch. Not only is he a fantastic novelist, but he's just one of the most generous writers around. And he's also very, very funny, which counts for everything. His first novel, Finn—the secret history of

Huckleberry Finn’s father—was named an American Library Association

Notable Book and was chosen as one of the year's best books by the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, and the Christian Science Monitor. It won the Philadelphia Athenaeum Literary Award and was shortlisted for the Sargent First Novel Prize. His second novel, Kings of the Earth—a powerful tale of life, death, and family in rural America, based on a true story—was named a best book of the year by the Washington Post and led the 2010 Summer Reading List at O, The Oprah Magazine.

His latest, Belzoni Dreams of Egypt is a novel in serial form--and I'm reading it now and it's extraordinary. It's also an idea so interesting, I'm going to let Jon tell you about it.

Tell us about what’s so different about Belzoni Dreams of Egypt? How is it a departure for you–and for most of publishing?

If the apparatus of publishing appreciates any quality in a writer, it’s predictability. Do more or less the same thing over and over again, and everybody stays happy. Everybody except the writer, in a lot of cases—including mine.

I’ve never been one to repeat myself. Shortly after Finn appeared in 2007, someone asked me what villain from literature I’d be writing about next. I answered that I didn’t want to be the guy who does that, and my questioner laughed and said, “The guy who does that makes a lot of money.” That’s probably true, and it might have been an easier course to take, but it didn’t interest me. So I went ahead and wrote two follow-up novels that were as different from Finn—and from each other—as they could be.

Belzoni Dreams of Egypt takes that fondness for variety to a whole new level. Finn and Kings of the Earth and The Thief of Auschwitz were all deeply serious, for one thing, and there’s nothing whatsoever serious about Belzoni. It’s a tall tale, an adventure, a romance. It’s a yarn narrated by a braggart who’s in love with the sound of his own voice. It’s a Saturday morning serial and a coming-of-age story full of carnival freaks and mummies and poison gas.

It’s the last book anybody ever figured I’d write, I can tell you that.

Why did you decide to release it serially and in parts?

Publishing is in such a state of uncertainty these days. Everything’s in flux—right down to the act of reading itself. Ebook or paper? Nook or Kindle? iPad or smartphone?

And more to the point: does anybody even read at all anymore?

Of the many forms that books take, big serious literary novels in particular tend to suffer most from the current dislocation. Readers have trouble finding them, for one thing, since book sections in newspapers and magazines are almost gone. Many folks have been trained by Amazon’s discounting model to think of reading as a kind of incidental activity that doesn’t take much investment of either money or time—and those folks are drawn more to the genres than to literary fiction. (I saw first-hand how the genres can still thrive when I self-published a science fiction novel, What Came After, under a pen name a couple of years ago and watched it rocket up to #8 on Amazon’s sci-fi bestseller list).

So I thought, “What if I take this unserious book and divide it into a half-dozen 50-page chunks and sell them for a dollar apiece, reaching casual readers at what ought to be a sweet spot of time and money?” Low commitment, low investment, low risk. Read it for a buck and move on. And Belzoni has the kind of pacing and narrative that will keep people coming back for the next installment—or at least I hope so.

The first installment, ”Rome,” is out now. The second, “Water & Bone,” arrives on July first, and the series continues through November. On December first I’ll release the complete novel both electronically and in paper.

Readers can check out an excerpt of Part One at Medium or find it at B&N or Amazon (Kobo and iBooks are coming soon.)

So what the heck is a fictional autobiography? What are the challenges of writing such a book?

I discovered Giovanni Battista Belzoni a long while ago in a book about British maritime history. He wasn’t much more than a footnote, but what little I learned about him fascinated me. So I did the usual Googling and then tracked down the one or two books (out of print) that had been written about him at the time. He was a colorful figure, a self-made archaeologist who pillaged Egypt while Lord Elgin was busy pillaging Greece. Born in Padua, raised in Rome, and educated by the Capuchins, he stood nearly seven feet tall and easily found work in England as a circus strongman. His strength and agility, along with his expertise in hydraulics and pyrotechnics, brought him to the attention of of Mohammed ‘Ali, the Pasha of Egypt, and from there it was short work to begin ransacking the Valley of the Kings.

The more I thought about Belzoni, the more curious I grew about what kind of outsized ego he must have had. I imagined telling the story of his life—more important, I imagined him telling the story of his life—and I saw that the modest amount that I knew about him could be turned into an entire lifetime’s narrative by remembering that he must have been an enormous bullshit artist. So there you have it. Belzoni Dreams of Egypt finds him on board a British warship, bound for the coast of Africa and his final adventure, nearly dead from dysentery, lying about his extraordinary life to an attentive seaman. The line between truth and fiction fades in a hurry.

Readers should be warned to take nothing at face value, and to look for signs of duplicity everywhere. In Belzoni’s voice, in particular. But elsewhere, too. One of the scholarly books quoted as introductory devices seems to have been written by a certain John Ray, Jr., for example—and if you haven’t reread your Nabokov lately, you probably should.

What surprised you about writing this?

How much fun it can be to write about true love. Belzoni and his wife, Sarah, were perfectly matched for one another and undertook many of their adventures side by side. Here he is, catching sight of her for the very first time:

“Heading straight toward me was the most ferociously beautiful young woman I had seen in all my life. Her walk was purposeful and confident, somehow easy and forceful and businesslike all at once, like the perfectly self-assured stride of a lioness. She was tall and slim and elegantly proportioned—not quite so tall as I, to be sure, but tall nonetheless—and she was gifted with the powerful shoulders and narrow waist of a lady pugilist. Her hair, lightly drawn away from her face and gathered loosely behind, was the color of honey mingled with chocolate. And her face—that face! its delicate shape! its clear-eyed expression!—her face was beyond improvement or description. As I watched her move toward me, I was possessed of a single thought: if the blind poet had known this woman, he’d have possessed his model for both the glorious Helen and the warlike Achilles in one matchless figure.”

You’ve taken such an unusual career path, that I’m wondering, what’s going to happen next for you?

I have a much more conventional novel in the works right now, a contemporary family story called How We Got Here, which is likely to be published in a more conventional way. Finn has been optioned for feature film development for a while now, and things have gotten extremely active over the last few months—down to casting and final script revisions and location scouting. I can’t give any details yet, but the people attached are extremely well-placed, enormously gifted, and hugely devoted to bringing that very complex novel to the screen. Kings of the Earth is under development too, as a limited-run cable series. I’ll keep you posted.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

First—in the context of these film projects—the waiting. Tom Petty was right.

Second, the idea that technology has given us so many opportunities to let projects like Belzoni take the shape that suits them best. This book is perfect for serialization, but where could that have happened in the last fifty years or so? Or the last hundred years, for that matter? Serialization in magazines and private editions worked for Dickens and Twain, but those days are gone.

Unless they’re back. And I’m betting they might be.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

How about, “How did it feel to write something that’s basically funny?”

Good question. My other books have actually had a good bit of humor in them, depending on where and how you looked. But Belzoni is light-hearted and funny from start to finish. I hope people are ready for it—by which I mean ready to grant me permission to do it.

On the other hand, moviegoers are only too happy to follow Woody Allen from the slapstick of “Take the Money and Run” to woeful depths of “Blue Jasmine.” So why shouldn’t readers follow me?

Friday, May 23, 2014

Elizabeth Eslami, author of HIBERNATE: STORIES talks about what the muse is not, whether or not writing is really fun, and so much, much more

Elisabeth Eslami is the winner of the 2013 Ohio State University Prize in Short Fiction and the author of the short story collection Hibernate, as well as the acclaimed novel Bone Worship. She teaches at the MFA program at Manhattanville College, and here, she's written a knock-your-socks-off piece on what creativity is---and what it isn't. I'm so honored to host her. Thank you so much, Elizabeth!

On Creativity:

No Room for Wings

1: Avoid wings and excuses.

Have no

patience for winged things, or easy things, or that which requires a spell or a

potion or circling three times fast, unless it’s you in your desk chair, where

you’ve been sitting for four hours, and now you’re spinning only to resume the

blood flow to your numb feet.

What

I’m saying is that the muse is a distraction, she is the enemy, and if you see

her, you’re best advised to gather her diaphanous gown and use it as a

slingshot to send her back to whatever version of Asgard she came from. The

muse is the one who tells you you’re not ready, that you need to sketch out

your character’s family tree before you write the next chapter. The one who

tells you to search the internet instead of writing because you haven’t done

sufficient research to know how much socks cost in 1942.

You

fell for that? You wasted a perfectly

good writing day waiting for some figment of your imagination to tell you you don’t have the authority?

Here’s

the thing about research. Whatever the time and place, it’s your version of that time and place. Put

the furniture on the ceiling if that makes sense in your story. You’re worried

about the Authenticity Police? When they show up, ask them how many books

they’ve written. Then point to yours. Then point to you, the authority. The

prime mover of worlds.

Given

the choice between a cookie or the promise of a cookie, you’d choose the

cookie. So why do you talk about the book you’re going to write instead of

actually writing it? At your age, whatever your age, you know what’s behind

you, the work you’ve produced, and you have a better sense of the shape of the

time in front of you, which is called Books Not Yet Written.

You

know what you see in front of you before you die, right? Books Not Yet Written.

What I’m

saying to you is, do rather than

pray.

2: What the muse also is not.

Every

semester, by dint of teaching creative writing, apparently I kill somebody’s

creativity. I’m always shocked when the student comes in to tell me this. It’s

like that scene in the movies when the expert who’s going to save the world

trips and shoots himself. It’s meant to

shock.

What

happens now? What do we do now that the creativity is dead?

Perhaps

you’re wondering how this tragedy happened on my watch. Well, I’ll tell you. I asked

what might happen if this student shifted the POV. If she worked to raise the

stakes. “It was going well,” the student says now, postmortem, all big eyes and

slumped shoulders and defeated sighs, “and then you made me do this.”

This

means that creativity is a Pamplona bull, running free in the student’s loamy

cranial pastures. Behold his might, the heat burning off his sweaty flanks. The

miniature inverse world in the orb of his eye. He’s wild when you pursue him,

and pursue him you must – another muse, with horns this time! – as he runs down

those streets, a clatter of keratin hooves on cobblestones.

“You

want me to do what?” the student asks. Revise? Make changes? To listen to you,

Professor, is to hobble him, neuter him, pen him up. Magic is what comes from

his unfettered flight through the streets.

But if

this bull is your muse, you’re in bad shape. What I see is a dying animal,

impaled and weak. What I see is you, breathless, chasing after something that

will fail you. Unchecked, unchallenged inspiration is useless. If you’re a

writer, nothing I throw at you can screw you up. You will rise to meet each challenge

because you understand your gift is that

strong.

If a

muse is anything, it’s a guard dog. Put a chain around his neck. Now put the

chain around you. Now chain you to the chair. If you move, the guard dog bites.

At first, you’re petrified. Then you forget he’s there. When you don’t go

anywhere for an hour, every single day, you’re a writer.

3: No one said this would be fun.

When

you hand your story back to me and I ask, how did it go? I’m pretty much fucking

with you. If you tell me it went well, I know you’re lying. If you tell me it

was hard, I assume you mean you were able to breathe while you worked on it,

and battle viruses – that your GI system was auto-piloting your digestion. Basically that all was status quo.

Because it’s supposed to be hard.

Because if it’s not, you’re doing it wrong.

Sit

back down, writer. This room is too small for wings.

All

right. You want wings? I take it back. The muse can be a turkey vulture. A

harpy eagle. Something with a beak designed for rending flesh, a head born red

because most of the time, it’s rooting through a carcass, festooned with

intestines, just, you know, surviving.

I’m sorry, am I grossing you out? Good. You know who’s focused? The damn harpy

eagle. Because killing, eating, surviving isn’t a game. Writing isn’t either.

4: Follow the blood.

At some

point, you will find something under all those lousy first and second drafts:

the good pages, the glittering scales of the monster that you know better than

to touch. Not only don’t you cringe when you re-read these pages, you find your

blood going to your chest supernova-style, geysering out to your fingertips.

You could read these pages a hundred times, and whatever it is that makes them

special will not diminish. You could have no faith in yourself, in what you can

say and do on a page, but even you

will read these pages and feel something weird worming above your chin. You’re

smiling, and you’re doing it because you know it’s good. Let those pages sustain

you. Pull them out when you need them, consult them for the promise of what

this book could be, even if it’s not there yet. Put them down on the desk, and

watch where your blood flows. That’s where you go next.

Conversely,

when you get lazy, follow the blood. It’s those twin boiling points on your

cheeks, the eternal threat of shame. Don’t embarrass yourself. You keep trying

to skip past the crappy paragraphs, but you know better. Your shame will wait

for you, in your cheeks, souring in your gut. Go back, eventually, and fix the

damn thing(s).

You owe

it to the better angels of your best pages.

5. Run from creativity.

Muses

aren’t the only danger. Beware the inspiration peddlers, the role players, the

“Find Your Voice” workshops. The fifty dollar a pop get-togethers where you sit

around washing down your write-a-novel dreams with Styrofoam coffee and

crullers and new friends. I’m not supposed to say that. I’m supposed to give

you an ice breaker or a fun exercise or a sing along, but I’d be cheating you

if I did.

What

you need is to do the work. What you need, forever and always, is the work.

No one

has the secret because there is no secret. Inspiration and creativity are

pretty words we use to describe the work but otherwise are completely useless.

If you let it, your mind will make a red herring out of those words. Your mind

wants you to play Bejeweled Blitz and click on a picture of Justin Bieber

pissing in a bucket. Override it. Take

control.

If you

only talk about the books in your head, you’re not a writer. Donuts and fun

times with nice writing groups are great, but they don’t make you a writer

either.

Did you

do the work? Did you write today? Words, not excuses.

Work,

not wings.

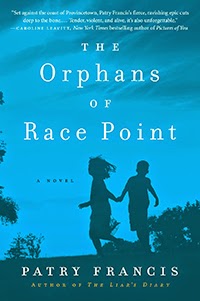

Patry Francis talks about The Orphans of Race Point, trying not to obsess, and so much more

Here are the facts: Patry Francis is a three time nominee for the Pushcart Prize, and has twice been the recipient of a fellowship from Massachusetts Cultural Council. Her first novel, The Liar’s Diary, has been translated into seven languages and was recently optioned for film. Now here is why you really need to know: Patry Francis is a genius writer who also happens to be one of the warmest, kindest people around. The only thing I'd like better than hosting her on my blog is having the chance to sit down with her over tea. Her book, which I blurbed, is truly haunting (Haunting being my litmus test) and I urge everyone to buy several copies. Thank you, Patry, for being here on the blog!

What sparked this book?

The Orphans of Race Point which I began

in 2001, has been a part of me for so long I really had to ponder that

question! Was it the spectacular landscape of the lower Cape? The close-knit

Portuguese community I admired, and into which my son had recently married? Or

was it some element of the long and twisting plot that came first?

However,

I didn’t have to think long before I saw the face and heard the voice that

haunted me from the start. It was Gus, the wounded, impulsive soul who

transforms a tormented childhood into a fierce compassion for others. Though I

didn’t know where his story would lead me, I saw him as both a child, hiding in

the closet where he was found nearly catatonic after his mother’s murder, and

as the man he became.

What surprised you in the writing and research?

What

surprised me was that Gus, my spark, my obsession, wasn’t my main character. In

the early drafts, the story began in what is now the middle, when Ava, a victim

of domestic abuse comes to him for help, triggering visceral memories and

bringing up the unresolved guilt from his past. Everything that preceded the

visit, including his complex relationship with Hallie, the girl he’d loved

since childhood, was revealed through backstory and it had the murky quality

that flashbacks sometimes have.

But Hallie

refused to play a secondary role. She knocked forcefully on the door of the

novel, just as she had when she first showed at nine years old, demanding

admittance to the house where Gus was staying. Six months had passed since his

mother’s violent death and he hadn’t spoken a word. In town and on the

playground, a rumor was circulating that he had become the victim of a feitiço, a kind of Portuguese spell.

Following in the footsteps of her father, the town doctor, Hallie attempts her

own cure by presenting him with two fish in a leaky plastic bag, and a

challenge to keep them alive. Then, she returns daily to read aloud to him

about an orphan who becomes the hero of his own story.

Once Hallie

assumed center stage, much of Gus’s story was filtered through her, first as a

precocious child and later, as a brilliant woman who felt it as strongly as he

did, and often understood it more clearly. I also discovered that she had her

own secrets to reveal.

This novel, for me, hooked me so emotionally. Did you feel

that hook while you were writing?

Yes,

definitely. Just this morning, I read a quote in a piece about censorship which

was printed in The Guardian. Jenn

Doll wrote:

“(Art) is not meant

to shield us from pain so much as offer a vessel through which we can cope,

grow and even move past tragedy.”

I

believe that one of the most sacred tasks of the writer is to inspire the

reader to feel, and we can only do that by experiencing the emotions ourselves.

Perhaps

because Hallie and Gus first appear as motherless children, I had a

particularly powerful connection with them. And then, as I say, we spent a lot

of time together. This is a long, twisty novel, spanning thirty years, and

stretching to include a large cast of characters. Over the years, I developed

empathy for all of them, even the most hopelessly devious.

What's

obsessing you now and why?

What’s

obsessing me is trying not to obsess--which is really the challenge

post-publication; don’t you think? Though it’s something like telling yourself

not to think about the color red,’m attempting not to look at numbers, or seek

daily validation that the book is doing “okay,” or to peek at too many on-line

reviews. Though I’m eager to get the word out in any way I can, I also know I

have very limited control over the novel’s fate. It’s time for the story and

the characters to speak for themselves now, to enter the hearts and minds of

readers and engage with them on their own terms.

I

remember debating a friend and early reader about what Gus looked like. Was he

short and muscular or a lean runner type? “Listen he’s my character. I know what he looks like,” I finally insisted,

thinking that settled it.

But

of course, I was wrong. If characters are to become real in a meaningful way,

they can only do it by interacting with a reader, one on one, and by being

imagined again as if for the first time. My job at this stage is to let go,

trust them, and move on to a new story.

What question didn't I ask that I

should have?

You should have asked how we

“met,” though you may not remember yourself! It was many years ago on the

wonderful, though now sadly defunct, writer’s forum, Readerville. I was in awe

to be talking with one of my favorite authors on-line. Then, as now, your

generosity to all who asked for advice or help, was an inspiration and a great,

great gift.

What's your writing life like?

Slow and laborious! I wish I

worked from an outline like many of my author friends do, or that I had a clear

sense where a novel is going before I began. But I tend to be a radically

organic writer. I only find out where I’m going by sitting down to write. The

surprises I encounter along the way are part of the fun, but they also throw

off any timetable I might set for myself. In the end, it takes many drafts

before the heart of the story emerges. And then it’s time to begin

revisions...sigh.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)