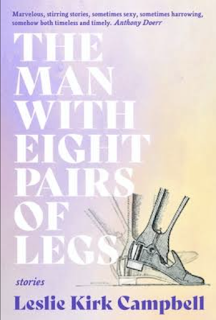

Leslie Kirk Campbell is the author of Journey Into Motherhood: Writing Your Way into Self-discovery. Her latest stunning collection of stories, The Man With Eight Pairs of Legs, has just come out. Visit her and learn more at www.lesliekirkcampbell.com

I always think that writers are haunted into writing their stories, or looking to write their way into an answer for some questions they have. Was it this way for you?

I am a writer richer in ideas than in characters. These ideas often arise from a question that is unexpectedly provoked by an image, a movement, a sound, or a dream. My story “Nightlight,” for example, arose from a vivid dream I had in which a middle-class woman, a wife, is looking out her bay window, surprised to see her husband walking away from her down the street, his arm around a young homeless man, the two almost glowing as the sun rises in front of them. Why did this man leave? I wanted to know. What drove him to make that decision? On another occasion, I heard the sound of someone cutting trees for hours while I worked in the old convent where I often go to write. I walked up the street and saw a woman standing alone at the top of her steep drive. I felt her sadness deep in my gut along with the sadness of the trees lying now in pieces on the ground. What sadness, I wondered, caused this woman to slaughter so many beautiful trees? I wrote “Tasmanians” to try to answer that question.

Story after story in THE MAN WITH EIGHT PAIRS OF LEGS was driven by my curiosity. What would it be like not to have legs? I wondered after seeing a row of fascinating prosthetics in a TED talk. And then, what makes a human human anyway? (“The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs”) How can a woman still love her philandering husband? (“Thunder in Illinois”). What might drive an abused woman to kill? (“Overture”) Each question, of course, connects with some key aspect of my own emotional landscape.

Your work made me think of that great book The Body Keeps the Score, about how our memories react to our memories, how the truth of what happened might be suppressed in our minds, but it always comes out in our bodies. Can you talk about that for us please?

The body does keep the score, as much as boulders along the sea or in the foothills hold the marks of tides, snow and wind. My own body has been repeatedly objectified, cut into by surgeons, its kidney bruised, an arm fractured, the body broken in half in a car accident. It has been assaulted, embraced, touched, and invaded with the threat of death. The body remembers.

That same body gave natural birth to two ten-pound babies (without epidurals), ran varsity track, and spent years studying modern dance, seeing itself in a wall of mirrors. I didn’t realize as I was writing these first stories of mine, that the body was so prominent in them. It took someone else to point out what I hadn’t seen. Over and over, as I attempted to write fiction, my body had been talking to me.

I believe in the emotional intelligence of the body, in the molecules of emotion. I believe we privilege the mind at the expense of listening to our own bodies. My body IS my story and the holder of my stories over time – even, it turns out to a time before I was born.

My maternal side of the family is Jewish, and immigrated through Ellis Island in the late 1800s. A couple decades ago, I went to the small town in Germany where my husband grew up. One night, on a stroll through his town, he pointed to a row of apartment buildings and said, in a neutral voice, “That’s where Kristallnacht took place.” Suddenly overcome, I sobbed sadness relentlessly in his arms. No one in my family had lived through WWII, but there it was, the grief of my people hidden, until then, inside my body. The body remembers.

My characters, too, are marked by their pasts and continue to be marked in present time: bruises that never totally disappear, scars, lesions, heroin tracks. In the “The Hermit’s Tattoo,” the main character tries to erase a tattoo with the name of a childhood friend he once loved. He rubs his skin raw with salabrasion for months, but her name is still there. For Mariam, the protagonist in “Tasmanians.” marks from her past are invisible, yet she feels the ancestral pain of genocide burning on her skin, as real as the fires that burned her grandmother’s family.

“City of Angels” arrived almost in one piece as I unconsciously repeated a particular movement in an improv class. We hold memories along our spines, in our groin, within the softest part of our wrists. I don’t believe that the brain is a closed container; it leaks and spreads, the nervous system reaching everywhere in the body with its rivers and tributaries.

Writing this first book of fiction, I discovered that to really know my characters I had to get inside their physical bodies. I did not want to simply be an authorial witness to their actions. I wanted to rummage around inside them, feel their heat, their aches, listen to their blood circulating – to feel in my body what it feels like to be them.

There is such a deep sense of longing in the stories, that I was wondering – what makes you long?

Perhaps I am a victim of my own restlessness. I lived in six different cities and went to ten different schools by the time I was 18. I longed to have a home like my friends who had lived in the same house since they were born. I was a song leader in high school cheering on the teams, but would imagine myself a prostitute in some foreign country. I was a ‘good’ girl, but I longed to be bad. I realized in my late 20s how male-identified I was and longed to know, finally, who I was as a woman.

At one point I was going to call my collection, Exit Stratgies, when I realized all my main characters seemed bent on escaping some form of imprisonment, whether literally, like the abused woman in “Overture,” or figuratively, from something in their past. Llyn and Grady in “Triptych” are refugees from Kentucky and New Orleans; Reiner in “Nightlight” is a refugee from his family farm in a small German town, and now wants to escape the mundanity of a middle-class job and marriage. My characters seem to seek something other than what they have, often taking dangerous risks to live out their passions, or to quell them.

I’m always curious (because I write novels, not short story collections) how writers decide which story goes first. Which one goes last? What was that process like for you?

When I started writing fiction in my late fifties, I simply wrote the stories I needed to write without any thought of a book. I used these first few stories to cut my teeth on fiction. But once I realized I had enough stories for a collection, and discovered a theme that could unify them, I had to come up with an order. I obsessively made lists in columns. Which ones were in first person, which in third? Which had a male protagonist and which a female? Where is the setting? Which ones are long and which short? Which ones ended with despair, which with hope? I didn’t want any two sequential stories to be too similar.

I had six long short stories and one short short. So I wrote a second one to balance things out. I put one in the first half of the book and one in the second half as a relief from the longer stories. I wanted this collection to be an orchestration, just as I did with each individual story, with variation of movement, texture, and feel. I chose to start with my title story, which I felt would be a great introduction to the collection’s emphasis on the body and longing for something else. I knew I wanted to end the collection on a very strong note. I knew, from attending more of my share of football games, that even after dazzling plays – passes, runs and interceptions – resulting in touchdowns along the way, how dejected I feel if my team ends in defeat. Filing out of the stadium, the exalting moments are forgotten. I needed my last story to be a winner. I chose “Triptych.” I wanted the reader to end their journey with a feeling of love, compassion, and hope.

You’ve been praised so highly for your prose – and rightly so – that I wanted to ask, do you read your word aloud to hear it as well as see it?

Yes, I do. In fact, I record each story and listen back with my eyes closed. I care, perhaps obsessively, about the music of the sentences, each paragraph a movement in a musical composition. I began as a poet. I wrote my first poem to the ocean in Capitola when I was ten, amazed that words could capture my unspeakable feelings of grandeur and awe. In college, I studied poetry from Spain, Britain, France, then traveled through Asia for a year picking up poetry books in every country, got an MA in poetry, studying modern Italian poetry at the Universita di Firenze. As a result, I understand the power of each sound in language, the magic of surprise juxtapositions. I’ve trained students to know what a poet knows about writing as a foundation for their writing in any form for nearly forty years. An image, a metaphor, a phrase or sentence can be thrilling to read, and I want it to be. I want the language to live on the page, it’s music – rhymes and rhythms, its silences, its musical scoring and orchestration. Language is the writer’s medium, just as clay is for the ceramicist, stone for the sculptor, and the body for the dancer. Too often, perhaps, writers take language for granted. But for me it is essential to love language like a poet, to be aware of its natural resources, to feel its exuberance. This is the kind of literature I get excited reading. Rhyme is not just the ‘cat in the hat’. In my stories there are echoes of idea, theme, and image, as well as sounds. I love this kind of layering and relish creating it, although it takes a long time…

What’s obsessing you now and why?

I am currently working on a second collection called Free Radicals. What I am exploring with these stories is the outlaw, the passionate outlier, and the meaning of freedom. I am re-reading Hannah Arendt on totalitarianism and reading Maggie Nelson’s On Freedom. In the long story Lilith that is the ground story for the collection, a Welsh woman wanders freely from place to place, making temporary friends along the way. As poor as she is, she seems not to have a care in the world. But how free is she? What has she lost? What has she gained? What about the love between a Nicaraguan landowner and a Sandinista revolutionary? A lesbian in a homophobic society? Is the lesbian free once she is allowed to get married (a kind of bondage) or was she freer as an outlaw? (I saw Thelma and Louise again recently, which also begs this question.). We are living through a time of angst around this question. What makes one person feel free, may injure someone else. Does anyone really have freewill?

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

Readers have commented on the richness of my stories’ settings and the way they are often grounded in a particular time in history.

Everything happens in a place, and that place cannot be separated from the characters, whether it is a city or a small room with mosquito nets over the bed. I am a firm believer in the power of sensory detail: smell, sound, touch. Together these details create a fully dimensional world. The small-town Colorado setting of “The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs” feels critical to the story of Harriet and Callahan with its bounty of churches (the “good”) and prisons (the “bad”) and its dramatically beautiful mountains and gorges. In “The Hermit’s Tattoo,” the wild fires arrive in sheets over the rolling hills. In each story, there is strong interplay between the character and the place they are in. These descriptive details invite the reader to thoroughly inhabit the worlds I have created for them – to smell the eucalyptus tar along with Mariam in “Tasmanains;” reading “City of Angels,” to feel the salt air and sunlight on their skin.

I am almost organically interested in the reality of history, of social context, of the way a character’s personal triumphs and tribulations do not occur in a vacuum, but within the fabric of a cultural and political era. What is happening beyond the confines of the characters’ individual lives puts pressure on their personal conflicts and choices. In some cases, it is a particular time in history I have lived through like the AIDS epidemic in the 80s, or I will spend hours researching to get the details I need so that the layers of politics, history, and the personal are all there together on the page.

No comments:

Post a Comment