T. Greenwood is amazing. A super talented photographer, she has also published twelve novels, including BODIES OF WATER (a finalist for a Lambda Foundation Award). She has received grants from the Sherwood Anderson Foundation, the Christopher Isherwood Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Maryland State Arts Council. And if that's not enough, she's won three San Diego Book Awards.?

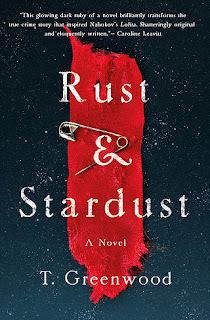

Rust & Stardust, the gripping, heart-wrenching novel of Sally Horner, the 11-year-old kidnapping victim whose abduction in 1948 inspired Nabokov's Lolita is already racking up the raves. Wanna see?

"Unflinching but compassionate, Greenwood deftly unravels the devastating layers of malice and carelessness that tore Sally from her family, but also the love and perseverance that eventually brought her home."—Bryn Greenwood, author of the New York Times bestseller All the Ugly and Wonderful Things

"A harrowing, ripped-from-the-headlines story of lives altered in the blink of an eye, once again proving her eloquence and dexterity as an author.”—Mary Kubica, New York Times bestselling author of The Good Girl

"An absolute treasure for bookclubs and the discussions it is sure to inspire."—Pamela Klinger-Horn, Excelsior Bay Books

Thank you so much for being here!

I was absolutely

haunted by this story. When was the moment when you realized, I have to write

this story?”

I read Lolita in

college and swooned. The idea that someone could write about something so

horrifying in such achingly beautiful language felt like a sort of magic. That

was the kind of writer I wanted to be.

Sally Horner was in those pages, though I didn’t know it at

the time, sequestered in a tiny parenthetical: (Had I done

to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to

eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?) Flash

forward twenty plus years, and I stumbled upon an essay by Sarah Weinman (“The Real Lolita” in

Hazlitt) which reveals the likelihood that Nabokov borrowed from Sally

Horner’s story in crafting the second half of Lolita. (Nabokov was known to scour newspapers for crimes that

echoed Humbert Humbert’s.) But what spoke to me more than all of this was the

photo accompanying the essay – the one of a golden sort of child sitting on a

swing. Eleven years old, abducted by a life-long criminal. She’d only been

trying to join a girl’s club at school – the initiation involving the theft of

a five-cent notebook from a Woolworth’s. LaSalle, recently released from

prison, “caught her” and was able to convince her that he was with the FBI,

that if she didn’t do as he said, he would have her arrested. At the time, my

youngest daughter was eleven years old – and while likely much savvier than

Sally would have been in 1948, I couldn’t help but imagine her in a similar

circumstance. That longing to belong to a group of girls so palpable, the blind

abeyance to authorities, the cusp at which girls at that age reside. I fell in

love with Sally first.

Then, when I began to

research this true crime, it felt as if it was a story I had been meant to

write my whole life. From the places LaSalle took her, to the people she would

have likely encountered, there were so many connections to my own experience,

it felt like serendipity.

I read everything I could get my hands on about Sally and

Frank LaSalle. I scoured newspapers.com, ancestry.com, and a whole host of

other sites trying to glean everything I could about the twenty-one months she

was in his custody. I also studied the various places he took her and

researched the historical context.

Ultimately, however, this is fiction. I had the skeletal

structure of the plot – the actual events and locations and timeline, but the

flesh is pure imagination. I had to dream myself into Sally’s character, her

mother’s character, those girls who set her on this tragic path. I also created

a number of fictitious characters (mostly women who unwittingly aided in

Sally’s survival).

While I made every effort to honor the “facts” I knew to be

true, I also took a thousand liberties (which is what fiction writers do) in an

effort to bring this story and these characters (as I dreamed them) to life.

I absolutely loved

that you told this story through the eyes of various characters—Sally’s mother,

her sister, Ruth. Was this always your decision as far as craft? I also absolutely

loved the kind bearded lady—where did she come from?

The first draft of this novel was written from an omniscient

and someone distanced point of view. I wanted it to be the story of not only

Sally but also of those around her, those impacted by this crime. However, with each subsequent draft (and

there were many), I zoomed in closer

and closer to the primary point of view characters. I actually wrote about

fifty pages from Frank’s point of view, but in a very late draft decided to

excise him. Nabokov had already written that story. I wanted this to be Sally’s

story, the story of her family, and the story of the communities she inhabited.

As for Lena (the bearded lady), she was a total surprise but

ultimately became one of my favorite characters. In researching the trailer

court where Frank and Sally lived in Dallas, TX, I learned that when the circus

was in town, the circus folks often stayed there. This was one of those amazing

gifts a writer gets, because all of a sudden, Lena materialized on the

page…this gorgeous, leggy hermaphrodite, who sees herself in Sally.

Reading this novel

made me completely unsettled, which is my highest compliment, by the way. What

was it like writing it?

As I said, the early drafts were written from a sort of

dissociated point of view. I was, frankly, scared to write this story, to be

inside Sally’s skin. It probably took four drafts before I even wrote her point

of view in. I knew that spending time with her, inhabiting her body, would mean

engaging in her suffering. I also knew that finding the balance between raw

honesty and delicacy was critical. I didn’t want this to be a lurid

exploitation but a reverent exploration of what she must have gone through.

Nabokov ends Lolita

in a different way than the way the true crime story here ended. Why do you

think he did that?

I recently read an essay about possible connections between Lolita and a story Salvador Dali wrote.

In the essay, Nabokov is said to have referred to gathering “bits of straw and

fluff” for his novels. I think that Sally really was one of those bits of straw

for him. His parenthetical about her suggests as much. But Sally’s story is not,

in the end, Lolita’s story.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

Here are my current twigs and fluff: a state “school” in

western Massachusetts called The Belchertown School for the Feeble-Minded, 1970’s

Florida, Weeki Wachee mermaids, the opening of Walt Disney World in 1971.

I have wanted to write a story set in the early 1970s

Florida forever. My family used to drive to Florida from Vermont every winter

(in a VW Bug no less). I love writing about lost places. I am also totally

captivated by abandoned asylums.

All of this comes together in my next novel, Keeping Lucy, which will be out next

summer.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

This is my twelfth novel, and people are often curious about

my process. One of the questions I am most often asked is if I write every day

or only when inspiration hits, and my answer is that I write regardless of

inspiration. If I waited for inspiration to hit, I’d never get anything done.

No comments:

Post a Comment