Thursday, August 28, 2014

My new favorite, Gabrielle Bell, talks about her graphic narrative strips, the compulsion to do diary comics, working in film, and so much more

I first saw one of Gabrielle Bell's astonishing comics (more like graphic narratives) in a post by the amazing Kate Christensen. I love Kate and trust her judgement and I ended up spending a whole afternoon reading Gabrielle's fantastic strips. Raw, honest, unsettling, and funny, each strip feels as if she's dipped inside the head of anyone who has ever been, oh, shall we say, a little bit anxious, very urban, with a touch of neurosis? (Hey, that describes me.)

Gabrielle began to collect her “Book of” miniseries (Book of Sleep, Book of Insomnia, Book of Black, etc), which resulted in When I’m Old and Other Stories, published by Alternative Comics. In 2001 she moved to New York and released her autobiographical series Lucky, published by Drawn and Quarterly. Her work has been selected for the 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2011 Best American Comics and the Yale Anthology of Graphic Fiction, and she has contributed to McSweeneys, Bookforum, The Believer, and Vice Magazine. The title story of Bell’s book, “Cecil and Jordan in New York” has been adapted for the film anthology Tokyo! by Michel Gondry. Her latest book, The Voyeurs, is available from Uncivilized Books. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

I'm so jazzed to host her here! Thank you so much Gabrielle, and thank you so much, Kate, for pointing Gabrielle my way!

Each of your strips reads like a little novel. Do you plan them out or do they just happen?

It's a bit of both, I think. I definitely plan things out, and hope that something else will happen too.

Being totally anxiety-ridden, I really responded to your strips about anxiety and nerves, and all that goes along with those evil creatures. Does drawing the strip help defuse any of anxiety's power? (God, I hope the answer is yes.)

Yes, I think it does, at least to an extent. Especially when people respond to it and recognize it in themselves. But...doesn't seem to cure it at all.

You've also made a film of one of your strips--about a woman who turns herself into a chair so as not to be too much of a bother. Genius! What was that process like for you?

It was exciting, but difficult. I'm glad I did it but working in film is so different than in comics. Drawing comics is having complete control over a very orderly small space that you create yourself, for the most part in solitude. Working in film is about collaborating, compromising and shepherding a lot of people to try to realize what is ultimately a collective vision, constantly surrounded by people. It takes two different kind of people.

Let's backtrack and talk basics. How and when and why did you begin the strip? How has writing and drawing it changed--and challenged you?

It is a compulsion of mine, to do diary comics. It is also the most simple and basic way to make comics, which are very difficult and complicated. Traditionally, comic books take whole teams to do the storytelling, penciling, inking and coloring. to do it all yourself takes years to get any kind of handle on. I do other projects, but in order to feel like I'm making some progress, so as not to get discouraged and give up entirely, I do these diary comics.

What's obsessing you now and why?

I guess I'm obsessed with my garden. I am pretty amazed that I'm able to bring food out of dirt. I spent all summer watching a flower turn into one big eggplant. It sure is easier and more refreshing than drawing comics. But I'm still into that, too.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

What would you do if you didn't draw comics?

I'd study music and theater and dance and I'd live a charmed life.

Maddie Dawnson talks about The Opposite of Maybe, teaching writing workshops, and what doesn't scare her

Maddie Dawson is actually Sandi Kahn Shelton (There, now her astonishing dual literary personality is out in the open!) Her last novel, The Opposite of Maybe, came out last April, but I can never resist talking to Maddie, and I'm happy to host her and her novel here again. Thank you so much, Sandi/Maddie!

A few summers ago, it seemed that everywhere I looked, my forty-something friends were turning up pregnant. What the heck? Were they having mid-life crises? Had they lost their minds? Were they regretting some hole in their lives that they thought a baby could fill? I wasn’t sure. But it set me on a path of thinking about life’s surprises—both the wanted and the unwanted—and the way that we tell ourselves the story of our lives, narrating to ourselves as we go along all of our limitations and our abilities.

So I wanted to write a story about a woman, Rosie Kelley, whose story was one of loss and not ever feeling truly competent in the world. Her mother had died when she was three, and she’d been raised by a grandmother who didn’t really want to be raising another child, and then after majoring in English and writing some poems that got published, Rosie had hooked up with a guy who made and sold pottery, and she kind of liked the itinerant, carefree life they had, with no marriage, no children, and the ability to do their creative projects uninterrupted. But after fifteen years, when one little thing happens—her potter guy leaves her to go open a museum in San Diego—she is set on a completely different course. When she discovers that she is pregnant, obviously the only thing that makes sense is to have an abortion. But it’s when she realizes what her future will consist of, living without her grandmother and not having a partner any longer, that she sees she needs to change the story she’s always told about herself.

I always love stories about people breaking away and seizing a moment that nobody else sees, and that is what happens to Rosie as she travels through her pregnancy, her grandmother’s dementia, and the friendship she forms with her grandmother’s caregiver, the sad and gentle Tony, whose wife is now happy in a lesbian relationship and who restricts his right to see his son. The makeshift, damaged family they cobble together—dealing with the pregnancy and Soapie’s illnesses and love affair, and with Tony’s son—brings about a life that Rosie never pictured for herself.

What surprised you about writing this book?

The way the relationships formed and re-formed themselves. I loved Rosie from the beginning, of course, since she was the one whispering the story in my ear—but I came to have a deep affection for her difficult grandmother as well, a woman who had struggled for independence back when women didn’t have many choices. Widowed after raising a rebellious teenager, Soapie thought she was free to live her life as a journalist, but when her daughter died tragically, Soapie found herself needing to wade back into the difficult waters of motherhood, knowing that this time she was going to do it differently, not be so permissive, not allow rebellion to ever take hold. The result was that Rosie was timid and found solace in other families’ lives, feeling that her grandmother would never truly love or understand her. As the two women come together in a kind of uneasy truce at first, Rosie discovers the secrets that her grandmother protected her from, and comes to see herself in a different light as well.

What scares you when you write?

Wow. What doesn’t scare me? The main thing, I guess, is that I might be too flippant. For years I was a columnist for Working Mother magazine, where I was writing what I thought were the deep, dark tragedies of domestic life: children who wouldn’t sleep, school projects that took over (like the time we had to motorize some raisins to represent puppies), and my efforts to measure up to a kindergartner’s exacting standards. I wrote these things seriously, and yet the magazine ran little cartoons next to them and called them humor. I always wanted to be dark and mysterious, to write about life and its pitfalls—of which I have had many. But I’m a Southerner, and I come from a long line of outrageous storytellers—truth was absolutely optional and sometimes a real detriment to a good story—and I think I’ve come to see life as a combination of the humorous and the tragic. My books tend to be promoted and marketed as frothy little romps in love and motherhood, and maybe I should be content with that…but it scares me while I am writing that I’m not truly expressing the balance of light and dark that I see all around me in life.

What’s your writing life like? Do you have rituals?

In summer, I move outside to my screened porch which is owned by a family of cardinals, and I set up shop there with my laptop and a large glass of iced tea, and I stare into the woods, watch the cardinals roll in the dust of my porch ledge, and write. First, of course, my ritual is that I have to play a game of 2048 (my latest obsessive game-playing, now that I’ve been able to come out from under Angry Birds and Spider Solitaire), and once that is out of the way, my novel will usually step forward and let me write it. If the phone rings too much (how many times can the Democratic National Committee call in one day? I love them, but it is an infinite number!), I pack up and move to Starbucks, which has the advantage of ambient noise, armchairs, and larger cups for the iced tea. Sometimes the sound of birds’ chattering isn’t enough, you know.

I read a quote that says that writing is 3% inspiration and 97% avoiding the Internet…and so I’ve had to resort to the Freedom app, which blocks out all Internet for as long as you specify. Sometimes it’s the only way not to cruise around on Facebook or checking out the latest antics of those would dance with the stars.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

For the past seven years, I’ve been teaching writing workshops in my home. Anywhere from seven to nine people come once a week, and we create this space where it’s safe to read and write from our deepest parts. I started this as something of a lark, thinking that I’d do it until it wasn’t fun anymore or until it started pulling me away from my own writing—and now I find that working with people who are mostly non-writers but who are so willing to try has given me such a different view of writing and what it means to be vulnerable. I am blown away by the work that gets done! It’s almost a healing antidote for those long stretches of lonely days spent living in my own head. Some of these writers say they have been badly hurt by teachers who long ago scolded them for their sentence structure or their spelling or told them they had nothing to say—and it’s fascinating to watch them bravely come out into the light and put words to these feelings they’ve carried around for so many years. I give a weekly prompt, and they go away and write it, and then come and read it aloud to the others, which isn’t nearly as scary as it sounds, when the audience is waiting for their words so eagerly.

I love that we, as writers, can create communities of other writers, that we can reach out and encourage, and listen to their stories. I make suggestions about commas and sentences, of course, and which thought would logically follow—but we are all often moved to tears by the stories and honesty and willingness to be open that I see around my table. My husband comes home from work on workshop days and now asks, “How many cried?” and when I say, “Everybody!” he knows we had a good, productive day. Sounds crazy, but there is just as much laughing.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have asked?

I’m always curious about how writers keep themselves going in a publishing world that is changing so much and asking so much more of us—in promotion and marketing, in social media and in outreach. I think you, Caroline, are so generous with all of us other writers and have truly been a role model in figuring this stuff out, while still keeping in sight the important thing, which is writing great books!

I knew from an early age that I wanted to be a writer—I sold my first story when I was six when my mother wouldn’t give me money for the ice cream man—and yet there have been a thousand times when I’ve wanted to quit and go to welding school instead. So how do we cope with all the uncertainties and not get swamped with feeling so alone? I think it’s people like you who are open and honest about your writing life and reach out with such love and good humor to all of us. So, thank you. I’m putting my welding school application on hold for the moment. At least until my new book—about a woman searching for her birth family while raising her fiance’s teenagers, is finished.

Sigrid MacRae talks about A World Elsewhere: An American Woman in Wartime Germany, how the writing changed her, and so much more

Many thanks to Viking for giving me this incisive, fascinating interview with Sigrid MacRae about her absorbing new memoir, A World Elsewhere.

Q&A with

Sigrid MacRae, author of

A WORLD ELSEWHERE:

An American Woman in Wartime Germany

A

WORLD ELSEWHERE is the extraordinary story of your parents: Aimee Ellis, an

American blue blood, and Baron Heinrich Alexis Nikolai von Hoyningen-Huene, a

Baltic German exile of the Russian revolution. Heinrich was killed on the

Russian front during World War II, leaving your mother with five young children

and pregnant with you. Having known this story of your parents for your entire

life, what inspired you to share this story now?

SM: A cascade of coincidences really. For years,

various objects acted as small, silent reminders of my family’s background. I

had read family memoirs of my paternal grandfather, an uncle, and

great-great-great grandmamma. I’d read my father’s letters from Hitler’s

campaign in France and his brief diary from the Russian front. But when a

beautiful Moroccan box with my father’s letters finally opened, it rattled all

my ideas about who he was. And when a rusty old file cabinet yielded a cache of

my mother’s early letters to an American friend, tracking her evolution from

giddy fiancé to expatriate wife to

war widow and refugee, I knew I had the makings of a book. I put everything

aside to work on Alliance of Enemies,

about the collaboration between German opposition of Hitler and the American

OSS, a valuable experience. When I went back to the family material, suddenly

everything ganged up on me. The letters had such immediacy, painting indelible

portraits of two young people—my parents-to-be—and the war that upended their

lives.

Once,

when I was a college girl, an elegant older woman looked at me as if she had

seen a ghost and said: “You are Heinrich von Hoyningen-Huene’s daughter.”

Having

grown up in post-war America, where Germans were unregenerate Nazis all, my

father, had always been something of the elephant in the room for me. A family

icon. but also my personal cross to bear because he was what made me a “Nazi,”

and was responsible for the gratuitous grief that came my way on that account.

I had been trying to keep that half of my parental equation at bay for years.

It was just one side of me after all, and the other side—New England Mayflower stock—was far more acceptable. But after all those years she

had recognized me anyway, not for being a Mayflower descendant, thank you, but she

had pegged me as the daughter of a father born in Russia into a brutal century,

exiled to Germany by the Bolshevik revolution, then dead before I was born. So

much for being Miss Mayflower.

Sooner

or later I had to deal with my puzzling provenance and it was well past time. I

read lots of history, and gradually it began to come together. Being a grown-up

helped, as did having spent a professional life as an editor. But stitching the

personal onto such an immense canvas was a

test.

Your

mother, an American who escaped her unhappy childhood by running to Europe and

marrying your father, was widowed at 37 and left with six children to raise on

her own. While she was brought up as a debutante, she learned to work hard on

the land, first in Europe and then once she moved your family to Maine. Did you

and your siblings, all successful in your own right, learn the value of a

strong work ethic from your mother? Where do you think she found that strength

and determination?

SM:

Adversity is a demanding teacher, but my mother did not quail—at

least not publicly. She absorbed its lessons with an unbeatable combination of

maternal instinct and fierce resolve. As a young woman she wrote to a friend: “life picked me out to spoil,” but then wondered

whether life wasn’t going to come along with the bill one day. When life

presented her with its bill, she had plenty of opportunity to develop the

required muscle.

People are more fluid than we imagine.

They, and we too, make assumptions about who and what they are; but they change

especially in dire circumstances. Sometimes when I was feeling particularly

beset or troubled as an adult, imagining what my mother was dealing with at the

same age always made me feel like a marshmallow. When I asked her how she did

it, she looked surprised. What was she supposed to do? Sit on her battered

suitcase and cry, with all six of us standing around her? As to where she

actually got what she used to call “plain gumption,” I still have no ready

answer.

As for learning from her, we knew we

were all in this together. Babysitting, construction jobs, waiting tables,

whatever—nothing elevated or grand that looks good on college applications—we just

worked to help pull the weight. There was also plenty of implied expectation

that we make something of ourselves, accomplish something.

SM:

My father’s letters from France mentioning German aircraft flying in gleaming

formation but hardly any French planes at all sounded alarmingly like

propaganda to me. Then I read Antoine de St. Exupéry, who was flying reconnaissance

for France, and to my relief, his account jibed perfectly. In the air above my father’s head, St.

Exupéry also saw so little French aircraft that he said they would fall to the

friendly fire that saw only German planes. He deplored France’s chaotic conduct

of the war, and he saw the same ribbons of rag-tag refugees my father saw. In another letter my father wrote of watching

the sun-browned bodies of young German soldiers splashing in the water of a

fountain in a French village. This really unnerved me, smacking as it did of

the adoration Aryan flesh. Yet according to his letters, the local population

seemed to agree with him. Then there was the fact that all mail from the front

was always censored. Anything critical of the campaign would have been deleted

in any case.

Sometimes the letters were disturbing

on a different, much larger scale: the devastation of my father’s exiled

parents; the hopes and dreams of my young parents falling prey to dreadful

realities and then so suddenly extinguished. It could be argued that the

extinction of my mother’s dreams gave her what we think of nowadays as a second

career—a different take and a new lease on life.

Was

there anything in the letters or your research that surprised you?

SM:

The letters were always utterly surprising; my father-to-be,

so young, so vibrant, so confident, amazingly well informed and educated. I

cannot tell you how much of his startling presence and character ended up on

the cutting room floor when I put the book together. He was also so self-aware,

so conscious of the label history had affixed to him. “Miss Mayflower flirting

with the Hun” he wrote, knowing the box in which the world had put him, but he

engaged this erroneous depiction with such disarming verve and humor. I’d often

heard about his charm, but the letters offered immediate, delightful specifics.

His touching, faithful recording of the messages of illiterate Russian POWs to

their families was devastating, as was his apparently growing awareness of what

awaited him, a fate that he had perhaps actually sought… And my mother’s young

letters seemed to me to have been written by a person I had never met. Reading

the manuscript, my oldest sister thought that the carefree young woman in some

of the early letters seemed to be an unrecognizable “flibbertigibbet.”

A

WORLD ELSEWHERE is an incredible combination of history and the personal

courtship and love story of your parents. It provides a moving personal story

within the profound historical framework of World War I, the Depression, World

War II, and beyond. Obviously your prime sources were family stories, but there

is a huge amount of major history here as well. How and where did you do the

research? Was there any travel involved?

SM:

Family documents were so important, but it is the fusion of the familiar with a

vast historical canvas that tells the sad story here. These people were trapped

between the parentheses of brutal century; bringing in enough historical

background (I thought of it as “canned Hitler”), without interrupting the

personal story was a constant challenge.

Most of my travel was restricted to the

New York Public Library. God bless its nearly bottomless supply of books and

information! And I was lucky enough to have a place to hang my hat (and keep a

shelf of books) at the Library’s Wertheim Study. So many wonderful titles that

never leave the library were consistently available to me. Individual titles

may not have been critical, but in the aggregate they were invaluable.

Apart from some internet travel back to

the Baltics, to the family farm in Germany, even to the Vuoksa River in Finland—some

of it extraordinarily evocative—my travel was limited to my mind’s eye. The

major exception was a trip to St.

Petersburg, part of my ongoing search for “home,” with my Grandfather’s memoir

acting as guide. It was fascinating, but yielded only the realization that home

was not there anymore.

You

were very young when your mother moved the family to her native America. Your

older siblings had a very different childhood from yours. Do you feel you were

raised in a different world from your brothers and sisters?

SM:

Yes and no. My oldest brother is more than 13 years older, and to a

considerable extent, my older siblings’ formative years were spent in a very

different world. They had real memories of the places and people I remember

only as tiny snapshots, with no running narrative. My real memories began en

route to America. But my mother took

great pains to keep my father, family contacts, language and cultural patterns

alive. One result of this was my feeling of being “in this world, but not of

it,” a feeling that was a double-edged sword. Sometimes it still is, but I now

appreciate the other edge of the sword. Now it has actually become an advantage,

something I never understood as a child

Your

childhood without a father must have been difficult. Heinrich’s family was very

close; did your mother speak of him and his family that remained in Europe? Did

your father’s side of the family visit after your mother moved you to America?

SM: Being without a father did not feel

like a hardship; I was little, I lived in whatever the reality was. I probably

never fully realized my fatherless state until I heard cousins consistently

talk about their mother and their father. So at 2 1/2, I told my mother: “You

are my Mami and my Papi.” My older siblings had lost their father; for them, being fatherless was a very different

thing. But they were hardly alone; Germany was awash in fatherless children at

that time.

My mother kept my father and the rest

of his family very much alive for a long time, writing consistently to everyone,

sending packages. She was often in Europe, and took me back for a year when I

was 12. She brought aunts and friends to the U.S. Later generations of second

cousins and grandchildren came too. Being in New York with an extra bed gives

me major points with family visitors.

How

did writing A WORLD ELSEWHERE change you?

SM: I

learned that there is not one history, but thousands, a story textbooks will

never tell. I learned that life is much more complicated than we ever imagine,

especially when large-scale history intervenes. I hope I’ve learned the lesson

that walking in another’s shoes is supposed to teach us: compassion, and the

importance of trying to understand when thoughtless, knee-jerk judgment is a

much easier response.

Oddly enough, I’ve also overcome my

vague, if pervasive rootlessness, and discovered that these days, home is not

at all what it was for previous family generations, but essentially home-made.

And maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

I hope I may also have paid a debt of

gratitude to my mother, my father, grandparents—to all who went before, through

loss, exile and misery, and endured.

What

do you hope readers will take away from A WORLD ELSEWHERE?

SM: An awareness that things are

not always what they seem, that there is room on the historical spectrum for

more than just black and white. That breaking the appalling cycle of exile,

war, displacement and misery that afflicts the world, now as much as then,

demands a break from the simplistic, complacent moralism that lurks everywhere.

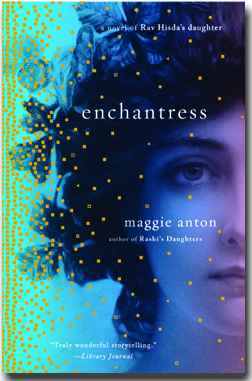

Maggie Anton talks about Enchantress, regrets on being a novelist, and so much more.

Maggie Anton is the award-winning author of historical fiction series "Rashi's Daughters" and "Rav Hisda's Daughter." She is a Talmud scholar, with expertise in Jewish women's history. Anton speaks to Jewish organizations all over the country about the research behind her novels, and her wonderful new novel, Enchantress, is hot off the presses this coming week. But let's be honest: I also wanted her here because you've never met anyone as warm, or welcoming, and doing events with her is always so much fun. Thank you, Maggie for being here!

What sparked this novel?

While studying Talmud, which I’ve

been doing for over 20 years, I came across a curious passage where Rav Hisda’s

daughter is sitting in her father’s classroom when he suddenly calls up his two

best students and asks her, “Who do you want to marry?” Astonishingly, she

replies, “Both of them,” and more

astonishingly, she is considered a prophet because that is what ultimately

happens. First she marries the older one and later, after she’s widowed, she

marries the other.

I couldn’t get this audacious girl

out of my head. How could she say ‘both of them,’ when asked which suitor she

wanted? I had to tell her story.

What was the research like?

It was quite a challenge. True

there were some books that dealt with the history of Jews in Babylonia, but

since my characters were only known from the Talmud, most of the information I

needed came from there. The English translation ran 72 volumes – with no index.

But it was incredible to learn all these great things about how the early rabbis

and their families lived, things very few people know about. Despite the

importance of the Talmud, third and fourth century Babylonia is definitely a

“black hole” in Jewish history. Nobody studies it.

What surprised you the most?

That magic was so

prevalent in these times, that the Talmudic rabbis and their wives cast spells

and wrote incantations, and that this was completely accepted. In the case of

healing magic and protection from demons it was even approved of, and women

were a big part of it.

Was there anything you found that changed the course of the

novel as you were writing it?

When I discovered

that Rav Hisda, his daughter, and her second husband all practiced sorcery, I

realized that Jewish magic was going to play an important role in this series.

My previous plot was going to involve all sorts of palace intrigues between the

ruling Persian nobles, Jews, and early Christians – a la Game of Thrones. That idea was abandoned and replaced by my heroine

first learning to become an enchantress, and then, as her power grows, the

challenges she must face from those who stand in her way. Eventually I had her

battling a jealous evil sorceress, Ashmedai King of Demons, and even the Angel

of Death.

What's your writing life like? Do you have rituals, do you

outline?

I do most of my

writing at night when I’m free from interruptions like phone calls and emails;

I’m often up way past midnight. A typical day starts with me lying in bed,

half-awake, imagining upcoming scenes. I find that my mind is most creative

during this controlled dream-like state. Eventually I get up, eat breakfast and

read the newspaper before heading to my computer. Then there’s email and other

online tasks like Facebook, Goodreads, and my blog to deal with – and now

there’s Twitter too. I work at home, so that makes me in charge of laundry,

cooking, shopping, and caring for grandchildren when they’re sick or out of

school/daycare for some reason. If I’m lucky I start writing in the late

afternoon.

I use a broad outline, more of a timeline,

to keep the scenes in place and make sure nobody is pregnant for 18 months or

things like that. But the outline changes as I think of new plot points and

drop old ones, and sometimes the characters take off in directions I hadn’t

anticipated.

I don’t think I have any rituals.

When we last saw each other, you mentioned that you might

not write another book. I can't imagine that! Is this true?

I also admitted

that there was some characters and a story chasing around in my mind, one that

refuses to leave. So I’ll probably write it, but there’s a difficulty in that I

will need some legal permissions before it can be published. So I don’t know

what will happen.

What's obsessing you now and why?

Besides this new

story that’s driving me crazy, I’m now consumed with promoting Enchantress. An author’s work isn’t

finished when the book is written, not if she wants anyone to read it. I

learned so many amazing things about Talmud and ancient Jewish magic, including

women’s place in them, and I want to share these with the many Jewish women’s

organization who will appreciate them. So I’m obsessed with contacting every

synagogue sisterhood and Hadassah chapter I can find and offering to speak at

their meetings. That’s how I made the first volume of Rashi’s Daughters, which I self-published, so successful that Penguin,

Crown, and Harper-Collins had a bidding war for the second and third volumes.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Do I have any

regrets about becoming a novelist? Obviously the answer is “yes.” I didn’t

start working on Rashi’s Daughters

until I was almost 50, and for the previous 40 years I was a voracious reader

of fiction. No favorite genre; along with literary fiction I devoured SciFi,

thrillers, murder mysteries, fantasy, historicals, even children’s books.

After I began

writing, my love affair with novels soured. It became increasingly difficult to

lose myself in the story as I learned to recognize the craft behind it. If a

book was really good, it depressed me because I knew I could never write so

well. And I lost patience quickly if it was bad or even mediocre. Worse, my

style would become contaminated by whatever novel I tried to read. Before the

movie came out, my daughter insisted I read The

Help, but it wasn’t long before my medieval characters were talking with a

Southern accent.

Monday, August 18, 2014

Edan Lepucki talks about California, Colbert, being on the motherflippin' NYT bestseller list, writing about difficult women, and so much more

Say you live on Jupiter and you know nothing about what's going on in the American book business. Say you never watch Stephen Colbert or pay attention to any magazine, newspaper or media. If that's true, then you wouldn't know the amazing story of debut author Edan Lepucki. Her novel California, was championed on the Colbert show and because of the "Colbert bump"--and also because the novel is so damn good--it soon hit the NYT bestseller list and she became justifiably famous.

But Edan has other accolades! She's also the author of the recently re-released novella, If You're Not Yet Like Me, The Los Angeles Times has named her a Face to Watch for 2014, and California is also part of the Barnes & Noble's Discover Great New Writers program.

And most importantly, Edan is really warm, funny and a brilliant talent. I'm not Colbert, but I'm thrilled to host her here.

And most importantly, Edan is really warm, funny and a brilliant talent. I'm not Colbert, but I'm thrilled to host her here.

I always am fascinated by the origins of books. What sparked

California? Did anything change and surprise you in the writing?

I fear I have told this story too often in recent weeks, but

it's true, so here it is: I was driving down Sunset Blvd. one night and the

streetlights above me had gone out. That stretch of boulevard was so creepy in

the darkness and it got me thinking about what LA would be like if all

services--streetlights street repairs, schools--ceased. I starting conjecturing

about what would have to happen to get to that point. At the same time, I

had the phrase "post-apocalyptic domestic drama" sliding back and

forth across my brain; I loved the idea and wanted badly to read such a

book. From those two moments, the story of Frida and Cal, escaping from

LA to the woods, came into being. Many things along the way surprised me:

stuff about Frida's brother, Micah, who was a suicide bomber at the Hollywood

and Highland Mall in LA; about Frida's family back in LA, about their

relationship and its struggles and secrets...so much! I don't plan ahead,

so much of the story is generated as I go.

I found the world's coming apart--and rag tagging it together,

alarming and disturbing, particularly in some of the parallels to life today.

Do you think the human race will survive? And at what cost?

I wanted the future to feel uncomfortably close to our own, so

that the reader felt afraid and complicit. I certainly entertain dark

thoughts on a regular basis, and recent events--from the horrors of Ferguson,

MO, to news of the bad drought in California--make me worry about our fate as a

species. But, then again, I think every generation has worried about the

future, and there is also so much compassion, ingenuity and love among

us. It hasn't all been horrible, has it? Ursula LeGuin has said

that science fiction writers don't predict the future, but describe the

present. I agree--I'm a writer, not a psychic. I have no idea what the future

holds for us!

I also deeply admired your portrait of a relationship. Cal and

Frida are so well-drawn, they breathe on the page. What kind of character work

do you do?

Thank you! I read for character, and it's why I write,

too. The "domestic drama" part of "post-apocalyptic

domestic drama" was what interested me most about the story, and I really

loved learning who Frida and Cal were. For me, characters in fiction

should feel wholly real, and the reader should feel like the character's life

precedes the story, and will continue long after the text ends. I tend to

build character through thinking/daydreaming about them; writing them into

being through scene; and really trying hard to inhabit the character's

consciousness--seeing the world as they would, using the language they would

use. The shifting perspective in California helped me to understand the

differences between Frida and Cal, too. I also wrote a ton of flashbacks for

both that ultimately didn't make it into the final draft; writing their past

helped inform their present.

What's your writing life like? Do you outline? Do you follow

where your pen takes you? Do you have rituals?

I write four times a week when my son is at daycare, from about

nine to noon; after that I must devote the rest of my child-free time to

teaching work. I don't use an outline, but prefer to work from

intuition. I turn off my Internet. and write directly into my laptop while

listening to music on my headphones. After I've written a scene, I

go to my notebook and take notes by hand about what I've written, what it

means, and what might come next. I am usually just a few scenes ahead of myself.

I like to read work aloud as I go, and fiddle with sentences/imagery. I

like to have coffee nearby!

So how has your life changed since the absolutely amazing

Colbert bump?

In some ways, it's changed a lot. I just returned from a big

tour where I was in a different city every night, and had the opportunity to

meet so many great booksellers and readers. I was on the motherflippin' New

York Times Bestseller List! That totally blew my mind. I still can't

believe it! I feel the whole experience has given me the freedom to write

my next book without worrying if a publisher will buy it. That's such a

relief--I feel like I can just write and write. In other ways, my life

feels exactly the same! I still have to juggle parenthood with writing,

and I still am slammed with occasional bouts of insecurity and misery about my

work. Life is life is life. I am glad to have my novel-in-progress

to return to; I am looking forward to returning to the cave...

What's obsessing you now and why?

I am writing a book with two complicated female characters. The

phrase "difficult women" has become an obsession for me of late. I

recently fell in love with The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton and am now

reading The Custom of the Country. I love Lily Bart and Undine Spragg--what

complex, difficult, unlikeable, sympathetic, amazing characters!

Tony Earley talks about his brilliant new collection of short stories, Mr. Tall, being sentimental and sad, ghosts, and so much more

The stories in this stellar collection take place in the South, so I

want to know why? What draws you to the South?

Aside from the three years

I spent freezing in Pittsburgh while my wife was in graduate school, I've never

lived anywhere else, so I don't know enough about any other part of the country

to write about it as well as I would want to. If I were to write a story set

in, say, Maine, all the characters would still sound like North

Carolinians.

What I love so much about your writing is the sparks of humor in the

stories, the strangely wonderful way of looking at the world that is as

surprising as it is original. Do you see the world the way any of your

characters do?

Only the sentimental, sad ones.

Some of the stellar reviews I read have mentioned that “you’ve grown

up.” My first response was, “what the heck does that mean?” before I realized,

of course, that they were talking about a more mature talent. Care to comment

on that?

I guess that finally being considered grown-up at age 53 is a

good thing. All my life I've wanted to sit at the big table. And while I like

being considered a mature talent, I hope it isn't code for beginning the long,

slow inexorable slide toward death.

What’s your writing life like? Do you have rituals? Do you map your

stories out or just wait for the Muse?

Most of things I write involve years of

thinking and self-loathing followed by sporadic bouts of typing. I suppose the

amazing thing about my process is that I've written five books without ever

appearing to write anything at all.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

My obsessions have been constant for

some time now: ghosts, tornadoes and vintage cars, particularly Alfa-Romeos and

Saabs. I got two of the three into "Mr. Tall." I sneaked in a Saab,

but it isn't vintage.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

Q: Which of your five

books do you consider your best? A: This one.

Sunday, August 17, 2014

Meet my new website

Not only am I novelist, a book critic and an online novel writing teacher, I'm also a freelance manuscript consultant. Got an unwieldy huge mess of a novel and you can't figure out why the center isn't holding? I can help. I've been doing this kind of work for years, and I love it.

Please find out more at my brand new website, designed by the writer Gina Sorell. www.carolineleavittconsults.com

Please find out more at my brand new website, designed by the writer Gina Sorell. www.carolineleavittconsults.com

Lesley Kagen talks about her just-out novella The Undertaking of Tess, her novel coming this March, The Resurrection fo Tess Blessing, PTSD, tinkering with writing a ghost story, and so much more!

Lesley Kagen is the New York Times bestselling author of Whistling in the Dark, Land of a Hundred Wonders, Tomorrow River, Good Graces, Mare's Nest, and her new novella, the Undertaking of Tess, (just out!) and the upcoming novel, The Resurrection of Tess Blessing, coming March 2015. Okay, okay, I couldn't wait until March and wanted to talk with her now. Thank you so much, Lesley--for everything.

Why write a novella?

Why write a novella? When I wrote the novel that's being released in March 2015-- THE RESURRECTION OF TESS BLESSING--I had to edit out much of the Finley sisters back story so it would flow better. Basically, I wrote the novella in order to tell more about how the girls came to be who they are when we meet them in middle-age because just about nothing intrigues me more than how people evolve.

Did anything surprise you about writing it?

I'd never written a novella before, so I was quaking in my boots. Once I got the feel of it, I absolutely adored it! I hadn't intended it to be as long as it is, but all sorts of things started to happen with the sisters that I didn't anticipate. I had to stop myself from turning it into a full length novel. On the other hand, I was so taken by the shorter form that I can't envision myself writing anything but now.

Your characters always seem so incredibly alive and rich. How do you go about structuring them?

Thank you for saying such a kind thing about my characters. I think they feel detailed because so many of them aren't fictional, but real people. I have PTSD, which in some ways is a blessing to a writer, the same way a cruddy childhood can be. Because of the way most everything and everybody imprints on my brain, it's not so much like I'm writing characters as hopping into a sensual Rolodex.

What's obsessing you now and why?

I'd like to revisit the Finley sisters, who I fell so in love with. I'd make it historical fiction again, set during the same time period as the novella (1950s) because I'm nuts about exposing the "good old days" for how they really way were, which was not that good at all. I'm pretty obsessed right now with writing anything that would flow easily from my heart, make readers laugh, but also intrigue them. Maybe a ghost story? A pint-size thriller? A middle-age psychological suspense crossover? Consider yourself warned Neil Gaiman!

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Is there any genre you wouldn't try?

While I admire those who can, I don't think I'd be good at all at writing sci-fi. The stories tend to be future based and I like hanging out in the past. Also, many sci-fi characters appear to very good at electronics and math, and I believe in the old adage, "Write what you know." Believe me, you do not want me to parallel park your car or balance your checkbook. The left side of my brain doesn't appear to exist. Hey...wait a minute! That's a pretty good idea for a sci-fi story!

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

Emily Arsenault talks about What Strange Creatures, balancing humor with terror, and how writing this book as a first time parent changed her, and so much more.

Emily Arsenault wrote her first novel in fifth grade. Her latest, What Strange Creatures, about family bonds, love, loyalty--and murder, is a stunner. She's also the author of The Broken Teaglass, In Search of the Rose Notes, Miss Me When I'm gone, and I'm thrilled to have her on the blog. Thank you so much Emily!

A brother arrested for murder, a sister who must prove his innocence, trying to save him when her own life is in turmoil. Where did the idea come from? What made you haunted enough by it to write a novel?

To start with, I was pretty sure I wanted to write a story about a jaded brother and sister, and I was pretty sure I wanted their relationship to have some humorous elements. In very small ways, I based them on my mom and my uncle, who live a block away from each other in the same New England town in which they grew up. (Like Theresa, my mother eats out a great deal. And like her brother Jeff, my uncle is very frugal and scavenges her doggie bags.) Of course, I couldn’t write a novel about these two simply sitting together at a kitchen table and making wisecracks. I needed for them to have a challenge that would jolt them out of their sarcastic passivity. So I threw a murder at them.

How did you find out about Margery Kempe, the medieval mystic, and how does she function in the novel?

I learned about Margery Kempe through a survey of early English lit class when I was fulfilling credits for English teaching certification years ago. I was intrigued by her unusual life—particularly the fact that she managed to convince her husband to allow her to take a vow of celibacy—and to go on pilgrimages by herself—after she’d had fourteen children with him. When I started What Strange Creatures, I knew I wanted Theresa to have kind of a quirky dissertation topic, so Margery Kempe came back to mind. It wasn’t until then that I read the entire Book of Margery Kempe (her autobiography—which she had a scribe write for her, as she was illiterate). I was happy to find some very odd stories about her life that I was eager to share with readers along the way. Additionally, I wanted Theresa to have a thesis topic somehow related to religion, so she could struggle a bit with the concept of faith. Margery Kempe gives Theresa an outlet—albeit a bizarre and at time frustrating one—for reflection during very difficult times.

For such a terrifying scenario, there is also a lot of humor in the novel. How did you balance the lighter moments with the darker ones?

That’s a good question. This is my fourth book. My first book, The Broken Teaglass, had a lot of humor in it. The two after that didn’t have all that much, and when I sat down to write What Strange Creatures, I was determined to make humor a priority again. I decided that what had prevented it in book two (In Search of the Rose Notes) and especially in book three (Miss Me When I’m Gone) was that the murder victim was too close to the narrator for anyone to have very much of a sense of humor. That is, the tragedy of the victim’s death overshadowed the tone of the book. With What Strange Creatures, I made the accused close to my narrator instead of the victim. Still a pretty grim situation, but nonetheless Theresa and her brother tend to survive tough times through humor and sarcasm. They can’t help but continue that habit even when the situation is more frightening than any they’ve ever experienced before.

What surprised you about the writing?

This was the first book I wrote as a parent. I started it when my daughter was about five months old and finished it when she was about eighteen months. I suppose what was most surprising to me about the writing this time around is that it doesn’t always need to be torturous. I had relatively short writing sessions to work with each day (or every other day), and learned to get right to work and enjoy it as an entertaining “break” from parenting rather than something to get stressed about. Writing novels is a joy and a privilege, not a burden. This is not to say it can’t sometimes be difficult, but I believe that before I had my daughter I perhaps took my writing opportunities for granted.

What’s your writing life like? Do you have rituals? Do you map your stories out or just wait for the Muse (that pesky Muse never shows up when you want him/her)?

I wouldn’t say I have rituals. I guess I have little tricks to get me through. For example, since I am a sugar addict, I sometimes reward myself with a Coke or a cookie if I’ve reached a certain word count by the end of a writing session. I do plan my stories to some extent. I usually know what I think my ending is going to be before I start writing in earnest. I don’t usually know many of the specifics of how I’ll get there. Sometimes I change my mind about the ending about two thirds or three quarters of the way through the first draft, and have to go back and do some serious rewriting. Actually, this is usually what happens for me, and it can be a painful process. Often it requires me to throw away a great deal of material. I suppose I have a Muse, but she is sort of a deadbeat Muse. She visits me about twice a year, when things are already going well anyhow.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

Ghosts! I am very excited about the novel I’m working on now, as it’s more of a haunted house story than a murder story. I’ve loved ghosts stories since I was a kid. This ghost story combines the unease of new parenthood with the suspicion that one’s family is “not alone” in their home. Lately, I’ve been wasting a lot of time watching mediums and ghost-hunters on Youtube. The book also has some historical elements that are new to me, and fun to research. Parts of the book take place in 1884.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

These were such great questions—I don’t have much to add. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to discuss What Strange Creatures!

Gabrielle Selz talks about Unstill Life: A Daughter's Memoir of Art and Love in the Age of Abstractions, having a father who was dubbed "Mr. Modern Art," the plight of artists today, and so much more

Gabrielle Selz is a writer and a live storyteller and her debut Unstill life is one of the most fascinating books I've read all year. She holds a BA in art history from the University of California, Santa Cruz and an MFA in writing from City College of New York, and she's worked in commercial television and on the political campaigns of two Greek democratic presidential candidates: Michael Dukakis and Paul Tsongas. She is the recipient of a fellowship in Nonfiction Literature from the New York Foundation for the Arts and a Moth Story Slam winner. She has published in magazines and newspapers including, The New Yorker, The New York Times, More magazine, Fiction, Newsday, and Art Papers. She now writes art reviews for The Huffington Post, and you can read her blog about art and life here.

I’m always curious when it comes to memoirs, how reliable memory can be. Certainly, we remember things differently as we age, and take on new perspective. While you were writing this memoir, did you find that you looked at things differently than you did as a child?

Unstill Life was a very complex memoir to write. There was so much art history involved and the threading together of so many stories. My memory is good, but it wasn't nearly enough, especially in the early sections of the book, which took place before I was even born. I was so lucky to have my mother's journals, her letters (she kept carbon copies of all her own letters as well) and the tapes my parents made to help me and to use as primary source material in Unstill Life. These were written at the time the events took place--they have immediacy and authenticity, that memory doesn't. As I wrote the book, my perspective on the events that took place in my childhood deepened. For instance, for many years I had been upset with my father for his role in the Rothko trial and for what I considered a betrayal of Rothko's children. It was so painful for me that I could barely speak about it. Yet, as I pieced the story together, I understood my father's motivations better. I came to known his character, his belief in what he was doing, the complexity of his action, as well as the complexity of the convoluted and interconnected relationships in the art world. The process of writing was so much more than my memory could possibly encompass. I first had to unravel the material, to separate it out almost thread-by-thread, to authenticate it with research and conversations. I also felt that I wanted to observe, to paint a picture, much more than stand in judgement of other people's behavior. I guess that, in itself, was a huge change in perspective. By the time I wrote the final draft of Unstill Life, I'd arrived at a place where I had no ax to grind. I wasn't impartial, I was just more interested in letting the story and the characters speak for themselves.

Your memoir offers up an amazing you-are-there portrayal of a New York City and a Berkeley that doesn’t exist anymore. To me, things seem more and more difficult in the art world, and artists are being displaced out of the city because of exorbitant rents. How do you see this impacting art itself? And is there a solution?

Yes, artists are being pushed aside in NY and the Bay Area now. Galleries are also being forced to move away from downtown SF due to the huge increases in rents because of all the tech money. It's insane. But it was always insane in NY. That's why they created Westbeth, to give artists a low rent place to live and work. So this problem has been going on for decades. Now, at Westbeth the artists there have aged in place and it's a naturally occurring geriatric community. The old folks there can't even afford to shop at the expensive grocery stores in the Village. I don't know what the solution is. They've cut so much funding from the NEA and from most art organizations. Maybe Kickstarter? Really, or Steven Colbert could go on television and ask individuals to help. I'm only half joking. If we want art in our communities we have to be willing to vote for it, and to raise and earmark the dollars for it. I do think the amazing thing about NY is its ability to rejuvenate. I've now seen at least three major booms ending in busts that have allowed artists to move back into neighborhoods and then the process starts up again. I hear that the new Williamsburg is the Upper East Side--above 96th Street. That gives me hope. But, now these neighborhoods are getting further and further away from the center of the city as the developers follow after the places artists have gutted and renovated.

It's still very rare for an artist to make real money. Because as artists ( as a writer I count myself in this group) we are so passionate about our work, people think we will do it for free. And we probably would, but we shouldn't have to. Since the 1970s, there have been artists doing performance and installation pieces on homelessness and squatting. Gordon Matta Clark did projects on land ownership and the myth of the American dream. It's fascinating how resourceful artists are. How they will turn anything, even (or especially) the predicament of their existence, into art. I know an artist out here in Long Island who's art project is living in a survival shack. The artist Sharon Butler has taken her canvasses off their stretcher bars so that she can work anywhere. She tacks her portable linen on walls . So there this imperative to make it work no matter what. Jackson Pollock took "Mural" off the stretcher bars to get it home and after that, paintings abandoned the frame. Max Beckmann painted on bed sheets after he fled the Nazis to Amsterdam during World War II. Creation is often born from pressures and constraints. In Tehran, Islamic artist Shadi Ghardirian, creates photographs where she exposes the code of Shahariah law--women there can not show their faces or be depicted in works of art--while at the same time still abiding by the restrictions. So she creates surreal images of women in decorative chadors their faces covered by their favorite kitchen utensil: broom, iron, pan, tea cup. These are amazing depictions. At once humorous and poignant, that explore the idea of censorship and religion, and comment on the role of women in society.

And now I'm going to say something maybe a little controversial. I think as artists part of our job is to find away to create art and survive--thrive if possible. Maybe that means not living in NYC or SF. I don't think we get to have it all. Choosing to be an artist is choosing to follow a passion that probably won't earn you the money that investment banking would. So choose with open eyes. Often, if we get what we want--like Westbeth--it doesn't solve the problems. It's still a struggle. The amazing grace of adulthood is learning to live in the space between wanting and having.

You’re exploring a time when art in America transformed itself, but so did people. Can you talk about that?

I think the art, as well as the culture, especially in NY and Berkeley, placed a very high value on self expression and self fulfillment. What was most important to these artists was to explore and express themselves at any cost. They had survived the depression and the war after all. The country was back on its feet, people were making money. And I think this desire for self-expression grew and transformed into becoming the dominate expression of the times. The expansion was powered by the boom in youth culture and by medias like television, which by the 60s, had become the dominate form of molding culture. Think of the changes that took place in the fist half of the 60s: The Free Speech Movement was born, the Civil Rights Act was signed, we landed on the moon, and in1965 the US government ruled that it was unconstitutional to prohibit married couples from using birth control. Sex was liberated.

What I witnessed at Westbeth and in Berkeley was the birth of a Utopian dream--the celebration of creativity and expansion, bohemian lifestyles, sexuality, pervasive drugs, etc., which evolved into the emergence of more hedonistic aspects. I wanted to explore this cycle, in art and in my life. Because it seems to me that the nature of the art of this period, was its need to break free and expand, its push towards infinity. I needed to understand how this need to push outward, to explore and break boundaries at all costs, effected my family. I wanted to understand the intersection of self-expression and family responsibility.

Your father was dubbed “Mr. Modern Art” and you’re a professional art critic. Do you find your sensibilities match your father’s in some way? Do you look at art and artists the same way he did?

Indeed, my father has deeply influenced my art education and sensibilities. He is such a great raconteur. But I am less of a critic than my father. In my writing, I prefer to explore a work of art. I prefer to engage and be with it. I write a lot about installation art because I find that I really enjoy stepping into an art object, becoming part of the evolving process. Dad was such a powerful figure in the art world. He was interested in discovering artists and making careers. He was also a curator, which I am not. I am foremost a writer and approach everything from that place. What's the story behind the object? What's the arc of the experience? Who is this person who created it? What is going on inside them? That sort of thing. I am more interested in falling into a work of art the way I fall between the pages of a book. I love finding myself inside some else's imagination. That's magic.

If you knew what you knew know about how things would change, would you have done anything differently while you were growing up?

Only one thing, not to be left at the Kinderheim. My parents abandoning my sister and me in a foreign country where we didn't know the language or know what was happening left its mark on both of us. It caused irreparable damage to my sister. Of course, that abandonment is indicative of my parents, and a great many of the other art world adults at that time. I don't know who I would have become without having survived that abandonment. Maybe less insecure, but also less resilient and resourceful. I guess we hope there is always a lesson or insight in a traumatic event and that we can be illuminated by it.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

I am thinking a lot about the power of structure, physical and otherwise, in our lives. Also, the architecture and cycles of utopias and dystopias. Abandonment vs oppression. What causes one to lead to the other.

And when I am not pondering these lofty thoughts. I am trying to enjoy myself and my son. It's his last year before he's off to college. The time is very precious to me. So we are obsessed with finding the right school! I see the theme of freedom vs structure is emerging here, too!

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

Everyone always assumes that it was painful to write this book. But in fact it was so much fun. Every morning I got to wake up and go into my office and enter this world--with this art! I was able to slip between the pages of my mother's journal, to visit with her before she became ill. I struggled to find a way to seamlessly incorporate so many voices, but particularly hers. Writing this book, bringing this world to life on the page, was one of the greatest joys of my life!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)